Duty, Faith, Love mark the life of Dr. Buford Usry, Iwo Jima survivor

In photo, then and now – Dr. and Mrs. Buford Usry of Brandon, Mississippi

By Whitney White, guest writer

November 2017 – “Clean up Iwo Jima.” It was February 19, 1945.

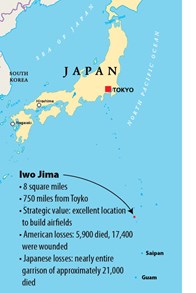

After 49 agonizing days at sea, Private First-Class Buford Usry and the Marine Spearhead Division had finally received their orders. Iwo Jima, a tiny Pacific island, was essential for emergency landing strips and fighter escorts who would later bomb Japan and end World War II.

Usry remembers being assured their mission “would only take three days.” But little did they know that over 20,000 Japanese soldiers awaited them in hidden bunkers and miles of intricate underground tunnels.

Before dawn that morning, Usry ate a Marine breakfast of steak and eggs, then watched their target come into view with the rising sun. Navy battleships began to blast Mount Suribachi, the dormant volcano that served as the Japanese command post.

Preparing for battle

Beyond the smoke, no life was visible on the desolate, black shores. The young warriors, many less than 20 years old, were ordered to get their gear, climb down the cargo nets, and settle into three waves of landing craft. Usry’s Higgins boat floated toward shore in formation in the third wave. For hours, the 45 men aboard stared ahead in silence. They circled in the water as the first wave hit the beach.

As the second wave ran ashore, the nightmare began. Once thousands of Marines were in Japanese sights, a deadly fire of artillery erupted. Unprepared for the attack, Usry’s company was sent in early. The circling boats stretched out in formation, one long wave.

“We knew this would not be easy when we saw boats around us taking direct hits,” Usry told AFA Journal.

“Bodies were floating in the water. Our boat had to push through them.”

Adrenaline took over as the ramp of the Higgins boat lowered. Holding rifles above their heads, they jumped into chest-high water and forged on.

“I jumped out and looked at my buddy beside me,” recalled Usry. “But he was gone. He never came up out of the water. It was against orders to go back for him. It’s haunted me that I couldn’t help him. I’ve tried to forget that.”

Deep, soft volcanic ash greeted troops as they stormed the beach. With every step, they sank to their ankles, slowing progress and becoming more vulnerable to the enemy.

“Casualties covered the beach,” he remembered. “We were pinned down with no safe place to hide. The Marine to my left was cut in half by a shell. Seconds later, the Marine to my right was also cut in half.”

Long way from home

Long way from home

Growing up, the only experience Usry had shooting a gun was nostalgic Saturday afternoons when his parents let him hunt squirrels with a .22 rifle. Never would he have dreamed he and his two brothers would be at war a world away from home, shooting high powered rifles, hunting men, and fighting for their lives.

On Iwo Jima, for the next four days, Usry doesn’t recall eating, drinking, sleeping, or using the bathroom.

“They never let up – not even at night,” he recalled. One night, a mortar shell fell at Usry’s feet in the fox hole he shared with his buddy. By the grace of God, the shell buried in the ash and failed to detonate.

“What do we do?” his friend whispered in fear.

“Roll out,” Usry replied. Knowing they’d be shot if they stood, they carefully rolled to their side, dug another hole lying down, and prayed to see morning.

Four days later, February 23, the fight to conquer Mount Suribachi was in full force. Securing it was key to winning the war.

“We were fighting down at the base when something caught my attention on top of Suribachi,” he said. He paused as tears welled in his eyes. “It was Old Glory. A sense of security fell over us and we fought harder. That flag means everything to me. We wanted to shout for joy. That was the first flag on Japanese soil, but we were still in battle.”

Usry and a few others took a wounded comrade to the aid station, but when they returned they were unable to find their company. Still, they managed to escape capture and reunite with their men. Usry recalls looking back at the flag again, and that would be his last memory of Iwo Jima.

Five days later, he awoke on a hospital ship, lying on a top bunk, where he was expected to die. His platoon had been hit by a shell. Shrapnel hit his gear and knocked him out, leaving him with a severe concussion but no major wounds. As he looked around the ship, he saw bodies piled everywhere. His first memory aboard ship was witnessing the burial of five Marines at sea.

He was soon carried to an unsecured tent hospital in Guam, and Japanese troops snuck down the mountain and opened fire on the hospital. Finally, he was transported to Hickman Air Force Base in Hawaii, where he was thrilled to learn that the Battle of Iwo Jima had been won, but he grieved to learn that his best friend since boot camp had died there.

Families sacrificed, too

Lying in the hospital, Pvt. Usry’s heart and thoughts turned often to Delores, the young wife he had married seven months prior to his enlistment. She was expecting their first child when he left to serve. Later, he was granted permission to return briefly from training to meet his daughter when she was two weeks old. He would have no more contact once he departed for war. But in a pocket of his uniform, there was always a photo of Daddy’s baby girl.

When military doctors discharged him from the hospital and returned his tattered combat uniform, he was overwhelmed to find that baby picture still in the pocket. He was given the opportunity to come home.

But Usry refused. As much as his heart longed to be with his family, he knew his duty was not done.

“To be free was worth dying for,” he said. For 12 months, he continued to serve in Japan on an occupation force and on remote islands until he was called into his colonel’s office, issued his Purple Heart, and ordered to go home.

Delores Usry hit her knees when she received her husband’s phone call from Memphis. In two long years, she had received only one communication – a telegram informing her that her husband was missing in action. She hardly recognized his voice; it had matured, and she was startled by the Northern accent he had acquired from fellow soldiers.

“She sacrificed during war every bit as much as I did, probably more,” Usry said. “I was fortunate, because I knew where my meals were coming from. She didn’t. She had to take care of the baby on very little money and often went hungry. She never told me that she was hungry until a few years ago. That hurt to hear.” The tears returned before he continued.

“It was my job to provide. I never knew she was hungry. War was harder on her, because she had time to worry. She didn’t know how she would make ends meet. She didn’t even know if I was alive.”

New lease on life

Those who haven’t experienced the horror of war might assume that soldiers on the field lived in constant fear, but Usry’s outlook was different.

“People ask me if I was scared,” he said. “No, there was no time to be scared. When we were children and our father told us to do something, we did it. Simple as that. War was no different. We were given a job, and we did it.”

After discharge, traveling back to Mississippi, he finally had time to think. Ironically, fear set in for the first time. How would he settle back into “normal” life? Could he provide for his family? What kind of job could he find?

He didn’t want Delores to have to work outside the home.

“That was my job,” he declared. “My one prayer throughout my life has been, ‘Lord, let me live long enough to take care of Delores.’”

He found work at a hosiery mill in Grenada, Mississippi. During this time, Delores gave her life to the Lord, and they began attending church.

“I realized I had only been a faithful church member my entire life,” Usry admitted, “not a faithful Christian.”

He later surrendered to the ministry. Along with three young daughters, the Usrys left the comforts of home and the financial security of a good job to move away so he could complete his high school and college education at Clark College.

“We had nothing,” Usry laughed. “She made the girls’ dresses from bed sheets. I don’t know where she found food, but we were never hungry. As long as we were together, we weren’t afraid. We learned to depend on the Lord. He always provided.”

Few people have had as many brushes with death as Dr. Buford Usry. However, at age 92, he is still blessing others with his testimony and his example. Life has often been a challenge, but he has been faithful because he serves a faithful God.

“I’d do it all again,” he said. “I have no regrets.”

Dr. Usry completed his doctoral degree in theological studies in 1987. He pastored 6 churches over 64 years. After 72 years of marriage, he and Delores have 3 daughters, 6 grandchildren, 15 great-grandchildren, and 6 great-great-grandchildren.

Dr. Usry completed his doctoral degree in theological studies in 1987. He pastored 6 churches over 64 years. After 72 years of marriage, he and Delores have 3 daughters, 6 grandchildren, 15 great-grandchildren, and 6 great-great-grandchildren.

He proudly wears an Iwo Jima veteran’s hat bearing the Marine emblem. He has fulfilled his duty to defend the Constitution and remain faithful to God, country, and family. He rejects the accolade of “hero” and declares that “the true heroes died on Iwo Jima.” American citizens today enjoy freedom at the expense of those who have sacrificed and those who still sacrifice to pay the high price it requires.

____________________

Honor their sacrifice

Author Whitney White and her husband Matthew, a bi-vocational pastor, homeschool their sons – Aaron, Aaden, and Aacen. Matthew was in the first wave of U.S. troops to enter Iraq in 2003. They offer these ideas to teach children to honor U.S. veterans:

▶ Have daily family prayer for veterans and active-duty military.

▶ Teach children U.S. history – read books and talk about the sacrifices of military personnel.

▶ Talk to veterans. Thank them for their service.

▶ Make cards/letters for veterans in the church, community, or a VA hospital.

▶ Attend Veteran’s Day programs and parades.

▶ Teach them to respect the flag and stand at attention when saying the Pledge of Allegiance or singing the National Anthem.

▶ Visit museums such as the National World War II Museum in New Orleans, Louisiana, or the National Museum of the Pacific War in Fredericksburg, Texas.