Matthew White

AFA Journal staff writer

Above, top to bottom: Ensign Jesse Brown in his cockpit. Ensign Brown takes the oath of office on board USS Leyte. Ensign Brown’s Official U.S. Navy Photograph.

May 2020 – “I think I may have been hit. I’ve lost my oil pressure,” radioed Ensign Jesse Leroy Brown as he crash-landed his Corsair fighter aircraft into the side of a snowy mountain.

Dreaming

Born in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, Brown’s dreams of flying began at an early age. The son of a sharecropper, he spent many hours in corn and cotton fields. Any time he saw an airplane overhead, he would share his dream of one day becoming a pilot. His family would laugh good-naturedly but never really took him seriously.

However, young Brown was serious, and he would prove it. He performed well in both athletics and academics in school, and when he graduated in 1944, against the advice of his counselors, he chose to attend a predominantly white college – a risky move for a young black man.

He was determined to study architectural engineering at Ohio State University, and despite being warned of the prejudice he would likely encounter, he persisted, resolved to overcome any such obstacle. That fall, he became the only black student enrolled in Ohio State’s College of Engineering.

He worked odd jobs while attending college to make ends meet. Having not forgotten his dreams of flying, he joined the Naval Reserve to help pay for his education. A poster recruiting students for a new naval aviation program excited Brown, but he was discouraged from applying and was told he would never make it to the cockpit of a Navy aircraft since there had never been a black Navy aviator.

Intent on being the first, he continued to press on until he was finally permitted to take the qualifying exams – five hours of written tests, oral tests, and a rigorous physical exam – all of which he passed with flying colors.

Training

Against all odds, in March 1947 Midshipman Brown became the first African American accepted into Navy flight school, in Glenview, Illinois, where he would either prove his flying abilities or fail to advance.

He successfully completed the process and advanced to preflight training where instructors did their best to weed out cadets who did not measure up to Navy standards. In June 1947, only 36 of 66 midshipmen in Brown’s class graduated from preflight training, Midshipmen Brown among them.

From there it was on to Navy flight training, during which Brown made a daring move that could have cost him his hopes of becoming a Navy pilot. Navy regulation at that time did not allow a cadet to marry until after graduation from the program.

No stranger to risk, Brown rushed home from training one weekend, married his longtime sweetheart, Daisy Nix, and was back in the cockpit Monday morning. He went on to complete flight training, and on October 21, 1948, Ensign Brown was designated a naval aviator, the first black man to wear “Wings of Gold.”

The story of the historic moment was picked up by Associated Press, and Brown’s picture appeared in Life magazine.

Fighting

Brown had come a long way from the Mississippi cotton and corn fields where he dreamt of becoming a pilot. Those dreams had come true, and he was now a section leader, flying a Vought F4U-4 Corsair. He was assigned to fighter squadron VF-32, which would ultimately end up in Korea assisting United Nations forces by providing air support for allied ground troops.

On December 4, 1950, Brown’s section was given the assignment of attacking enemies in defense of the U.S. Marines near the Chosin Reservoir, allowing the overrun Marines time to withdraw to a rescue point.

Brown’s Corsair was hit by enemy fire, and he was forced to make a crash landing into the side of a snowy mountain. His wingman, Lieutenant Junior Grade Thomas Hudner, who watched the crash, saw Brown waving from the cockpit but not exiting the wreckage.

With smoke rising from the shattered aircraft, Hudner knew if he was going to attempt a rescue he had to act quickly. There was nowhere to land safely. Risking court-martial, enemy capture, and his own life, Hudner made a split-second decision and belly-landed his plane about 100 yards from Brown’s.

Hudner discovered that Brown was stuck, his leg crushed and wedged between the equipment and the metal hull. He struggled to remove his friend, but to no avail.

Brown, aware that his time was fading, uttered his last words, instructing Hudner: “Tell Daisy that I love her.”

After a rescue helicopter arrived, the pilot and Hudner tried together to free Brown’s lifeless body, but realized their efforts were in vain. With daylight fading and the possibility of being captured increasing, they made the difficult decision to leave Brown’s body behind.

Saluting

Sending a team to recover Brown’s body was too dangerous due to the proximity of enemy troops. Instead, his shipmates decided to honor him with a “warrior’s funeral.” On December 7, 1950, seven fighters loaded with napalm flew over the crash site, made a wide circle, then draped Brown’s Corsair with a blanket of flames. The pilots rocked their wings in a final salute, then sped away from the fallen soldier’s final resting place.

Honoring

LTJG Thomas Hudner received the Medal of Honor for his heroic efforts to save a fellow soldier. Ensign Jesse Leroy Brown posthumously received the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Medal, and the Purple Heart. Not only was Brown the first African American Navy aviator, he was also the first African American naval officer to lose his life in combat, as well as the first African American to have a Naval Ship named after him – the USS Jesse L. Brown, christened on March 18, 1972.

Remembering

Countless stories like Jesse Brown’s are far too often unknown or forgotten. The commitment, courage, and sacrifice of those who gave their lives to secure freedom for their fellow citizens should never be taken for granted. For too many, the upcoming Memorial weekend will signify little more than the beginning of summer, a day off work, and cookouts.

Sadly, honoring fallen heroes is not commonplace any longer, and unless future generations are taught that their freedom was purchased at a great price, the true meaning of Memorial Day itself may become nothing more than a memory.

Teaching the next generation

• Visit and study national cemeteries and war memorials.

• Place flags and flowers on the graves of service members at a local cemetery.

• Research significant battles and discover the stories of heroes such as Jesse L. Brown.

• Theodore Taylor’s biography, The Flight of Jesse Leroy Brown, is available at online booksellers, and Taylor narrates a documentary, Jesse Leroy Brown: First African American Navy Fighter Pilot, available at YouTube.com.

____________________

AFA family resource

AFA family resource

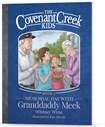

An excellent resource is Book Two from the Covenant Creek Kids series, Memorial Day With Granddaddy Meek. Read how a patriotic veteran great-grandfather’s heart is broken when his grandchildren have no idea what Memorial Day means.

As he remembers and grieves the loss of fellow soldiers from decades ago, his wife urges him to take the time to teach the children.

“Not today, dear,” he says quietly.

“Yes, today!” she exclaims. “If you don’t take the time to teach them, who will?”

This is a great book for parents and grandparents alike to read with their children to learn the history and etiquette of Memorial Day. The book is an original resource commissioned by AFA and authored by Whitney White, wife of Matthew White, who shared Ensign Jesse Brown’s story above. It will be available May 1 at afastore.net or 877.927.4917.

Review by Randall Murphree