Joy Lucius

AFA Journal staff writer

Above, "Smitty" and Louise Harris at their home in Mississippi. Inset, Captain Carlyle "Smitty" Harris.

November 2019 – 94 months.

2,871 days.

68,904 hours.

4,134,240 minutes.

April 4, 1965 through February 12, 1973.

That is exactly how long Captain Carlyle “Smitty” Harris spent in captivity as an American prisoner of war (POW) in Vietnam. But after 46 years, the now-retired Air Force colonel and his wife Louise do not consider that time wasted.

“Our values were strengthened through that time,” said Harris. “We now have a different outlook on things. Therefore, we gained from that time. And we don’t dwell on the bad things; we dwell on the good. So, the net effect on our lives has been positive.”

His wife agreed: “We know how blessed we are. We appreciate all the good things that have happened to us – our family, our home, and the freedoms we have. We have so many blessings.”

Gratitude and blessing were recurring topics when AFA Journal visited in the Harris home. The Harrises radiate with palpable joy while discussing that time in their lives, as well as the recent release of the colonel’s autobiographical book, Tap Code.

A communication code

Written in conjunction with award-winning author Sara W. Berry, Tap Code begins as Harris’s F-105D “Thud” airplane is shot down on April 4, 1965, near Ham Rong bridge at Thanh Hoa, North Vietnam. He became the sixth of hundreds of American POWs captured during the air war over Vietnam.

Detailing atrocities of his captivity, Tap Code is also a narrative of triumph, highlighting the secret code Harris shared with his fellow POWs. Accordingly, many of the 566 American prisoners finally released in the spring of 1973 credited their sanity and survival to Smitty Harris and the tap code he taught them.

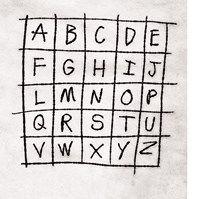

Garnered from one brief, providential conversation with an Air Force instructor, Harris’s secret communication code (see illustration to left) started with a simple alphabetical grid: Five rows by five columns, 25 letters, omitting the letter K.

Garnered from one brief, providential conversation with an Air Force instructor, Harris’s secret communication code (see illustration to left) started with a simple alphabetical grid: Five rows by five columns, 25 letters, omitting the letter K.

Tapped on a wall, a pipe, or any available surface, each letter became a number represented by two sets of taps. The first set designated the letter’s horizontal row, the second set its vertical column.

To greet a fellow POW with a friendly hello began with H: tap-tap (for second horizontal row); then tap-tap-tap (for third column.)

More than communication, Harris’s tap code helped fellow prisoners withstand barbaric conditions of thirst, hunger, isolation, and both mental and physical torture. It also became a lifeline for American POWs, binding them to each other and to life beyond captivity.

For instance, the POWs counted each day of imprisonment with surprising accuracy. Subsequently, holidays often compounded feelings of homesickness and loneliness.

In November 1966, Harris was relocated to Briarpatch, a remote and particularly harsh prison camp. With hands bound behind his back, Harris backed up to the wall of his 7x7-foot cell and began tapping to Ron Storz on the other side of the wall.

“I tapped, ‘Hey, Ron. I’m going to describe my Thanksgiving dinner. Then, you tell me what you’re having for dinner,’” said Harris. “So, Ron and I tapped on the wall all morning, playing our fabulous Thanksgiving game.

“When we finally ran out of ideas, I asked if he wanted to come and join me for this great Thanksgiving meal we had put together. Ron quickly tapped back and said, ‘I would, Smitty, but I’m all tied up today.’”

A conduct code

It wasn’t just humor and hope that the tap code offered POWs in times of trouble. It helped establish the chain of American command, conveying orders and information down that chain. Equally important, it provided solidarity for the POWs when interrogations worsened.

Harris described how each prisoner had multiple experiences of being dragged from his cell and forced to endure sadistic torture, sometimes for days at a time. When returned to his cell, broken and defeated, each man would begin receiving multiple tap messages of GBU – short for “God bless you.”

Those three letters reminded the broken man he was not alone. And per Article III of the 1955 Code of Conduct for Members of the Armed Forces of the United States, tapping out GBU helped POWs keep the faith with their broken and beaten fellow prisoners.

“The Code of Conduct became our goal,” Harris explained. “We were determined to return home with honor, having faithfully adhered to the Code.”

A commitment code

While Harris faithfully followed that code, his wife was equally faithful and committed to keeping her marriage and her small family intact while waiting for her husband’s return.

“I always believed Smitty was coming home,” said Louise. “So, I made up my mind early on that we would live as if Daddy was going to walk through the door at any minute. I wanted the children to know exactly what Smitty liked, what he thought was funny, and what he would not approve of.”

She managed to do that consistently for the entire eight years Harris was a POW. So, when he came home in 1973 to two preteen daughters and an eight-year-old son he had never seen, Louise said their family never missed a beat.

“I always told them how much Smitty loved to tease,” Louise explained. “Years ago, driving through Texas, he tricked me into looking for a jackadillo, supposedly a cross between a jackrabbit and an armadillo.

“I had told the jackadillo story so many times to our kids that he couldn’t pull it off when he tried out the same joke on them. They were ready for him.”

Harris was equally ready to enjoy his family and their life together. He vowed never to waste a minute he had left in life.

When asked if he had kept that vow, his wife quickly said, “He most certainly did keep his vow. He’s so hyper that he can’t sit still even now.”

Harris conceded to his wife’s reply with a knowing grin and a twinkle in eyes that belie his 90 years. It is almost as if time has stood still for the colonel.

In fact, both of the Harrises are healthy and vibrant, looking decades younger than their years. They are grateful to God for their health and for many other blessings – even those 2,871 days of captivity.

As Harris writes in the last lines of Tap Code: “Those eight years gave me time to sort out for myself the really important things in this life – especially my relationships with God, country, family, and friends. Life has been wonderful for me, and I am eternally grateful for every part of it.”

This Veterans Day, it is fitting that all of America give thanks for Col. Harris and his wife along with countless other armed service families who have sacrificed beyond measure to secure freedom in this nation.

And it is fitting to salute each of them with a hearty GBU: tap-tap, tap-tap / tap, tap-tap / tap-tap-tap-tap / tap -tap-tap-tap-tap.

Tap Code coming soon

Tap Code coming soon

See here for a daughter’s moving epilogue from Tap Code

by Col. Carlyle “Smitty” Harris and Sara W. Berry.

The book will be available from Zondervan November 5.